Transaction Isolation Levels

ACID

- Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability

Acid properties are a set of characteristics that guarantee the reliability of transactions in a database system.

Atomicity

- Atomicity ensures that a transaction is treated as a single, indivisible unit of work.

- Either all changes in the transaction are committed, or none of them are.

Consider a bank transfer where money is withdrawn from one account and deposited into another.

- Atomicity ensures that if the withdrawal succeeds, the deposit will also succeed. If any part fails, the entire transaction is rolled back.

Consistency

Consistency ensures that a transaction brings the database from one valid state to another. It enforces integrity constraints to maintain data accuracy.

If a database has a constraint that all customer IDs must be unique, consistency ensures that a transaction creating a new customer will not violate this constraint, maintaining the uniqueness of IDs.

Isolation

Isolation ensures that the execution of transactions is independent of each other.

- Even though transactions may run concurrently, the result should be as if transactions are executed in some sequential order.

Two transactions, A and B, both update the same row concurrently. Isolation ensures that the changes made by one transaction are not visible to the other until the transactions are committed.

Durability

Durability guarantees that once a transaction is committed, its changes persist, even in the face of system failures(e.g., power loss, crashes).

After a user completes an online purchase (which involves a series of database transactions), the confirmation is shown. Durability ensures that the purchase details are permanently stored, so even if the system crashes immediately after, the data remains intact upon recovery.

In summary:

- Atomicity: Transactions are all or nothing.

- Consistency: Transactions maintain the integrity of the database.

- Isolation: Transactions execute independently and produce the same result as if executed serially.

- Durability: Committed transactions persist even after system failures.

Dirty Reads

A dirty read occurs when one transaction reads uncommitted changes made by another transaction.

Example:

- Transaction A updates a row.

- Transaction B reads the updated row before A commits.

- If A rolls back, B has read data that was never committed, resulting in inconsistency.

Non-Repeatable Reads

a transaction reads the same row twice but gets different data each time

A non-repeatable read occurs when a transaction reads a value and, during the course of the transaction, the same value is modified by another transaction before the first transaction is completed.

Example:

- Transaction A reads a value.

- Transaction B modifies the value and commits.

- If A reads the value again, it gets a different result, causing inconsistency.

Phantom Reads

A phantom read occurs when a transaction reads a set of rows that satisfy a certain condition, but another transaction inserts, updates, or deletes rows meeting the same condition before the first transaction is completed.

Example:

- Transaction A reads all rows where age > 25.

- Transaction B inserts a new row with age > 25, which satisfies A’s condition.

- If A reads again, it encounters a “phantom” row that didn’t exist during the initial read.

In summary

- Dirty reads: Reading uncommitted data.

- Non-repeatable reads: Reading data that changes during the transaction.

- Phantom reads: Reading a set of rows that is later modified by another transaction.

Database Transaction Isolation Levels

In database management systems (DBMS), transaction isolation levels define the * *degree to which transactions are isolated** from each other.

These levels balance the trade-off between data consistency and system performance.

Read Uncommitted (Isolation Level 0):

Description: Transactions are not isolated. Dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, and phantom reads are possible.

Use Case: Rarely used in practice due to significant risks to data consistency.

Read Committed (Isolation Level 1):

Description: Ensures that a transaction only sees committed data. Prevents dirty reads but allows non-repeatable reads and phantom reads.

Use Case: Suitable for scenarios where dirty reads are unacceptable, but some inconsistency during a transaction is tolerable.

Repeatable Read (Isolation Level 2):

Description: Guarantees that a transaction can re-read its own reads and won’t see changes committed by other transactions.

- Each transaction has its copy of data where they update the data

- Once the transactions are committed then only the updates are persisted in the database.This is known as Snapshot Isolation.

- If two of the transaction concurrently change the same key to different values

- if the transaction is rolled back, then it is called Optimistic Concurrency Control.

- Prevents dirty reads and non-repeatable reads but allows phantom reads.

Use Case: Appropriate when consistency within a transaction is critical.

Serializable (Isolation Level 3):

Description: Provides the highest level of isolation. Ensures complete isolation from other transactions.

- Prevents dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, and phantom reads.

- a transaction holds read and write locks on any rows it references.

- It also acquires a “range lock” if a WHERE clause is used on a range so that Phantom Reads are avoided

Use Case: Ideal for scenarios where data consistency is paramount, even at the expense of performance.

Optimistic Concurrency Control we expect that concurrent transactions won’t change the same key.

So if that happens we rollback one transaction.

| Isolation | Efficiency | Isolation Level | Implementation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least Isolated(4) | Most Efficient(1) | Read UnCommitted | Single Data Entry | mains a single entry in DB and overrides upon updates |

| 3 | 2 | Read Committed | Changes into Local Copy | local values of a Tx is kept until committed in the end |

| 2 | 3 | Repeatable Read | Versioning of unchanged values | maintains all the version of changes |

| Most Isolated(1) | Least Efficient(4) | Serializable | Queued Locks | Causal Ordering. Same Key Tx’s must be ordered else concurrent |

Distributed Transactions

How it’s handled

2 patterns for handling distributed transactions

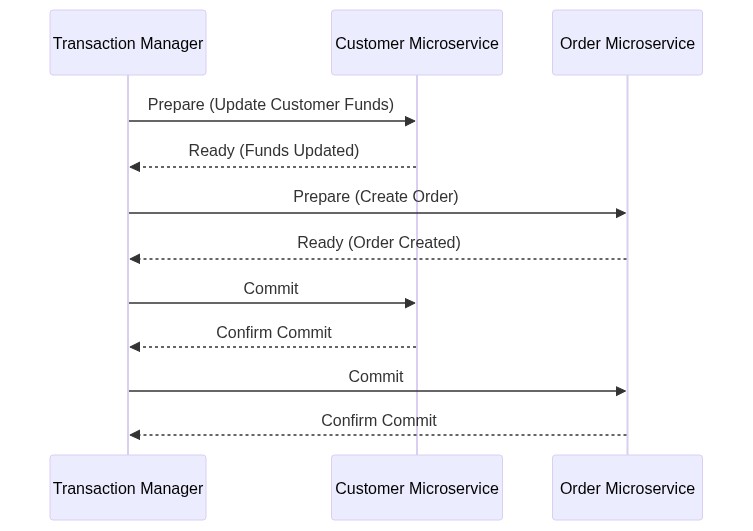

- 2 Phase commit - prepare & commit

In case of a failure during the preparation phase, the Transaction Manager would instruct all involved services to roll back their changes.

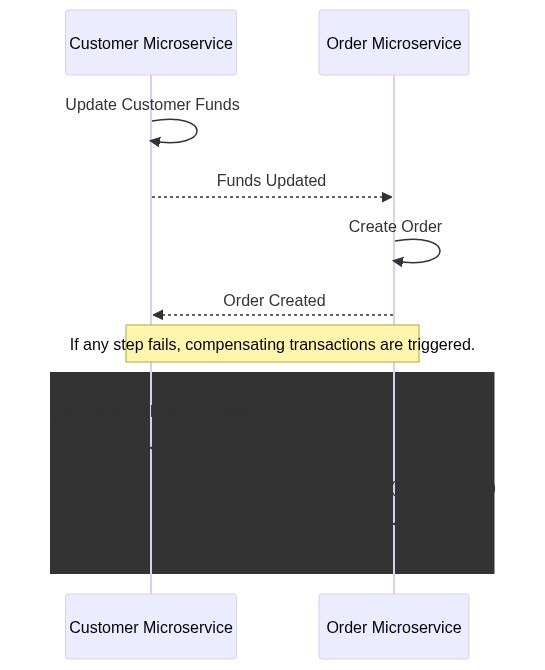

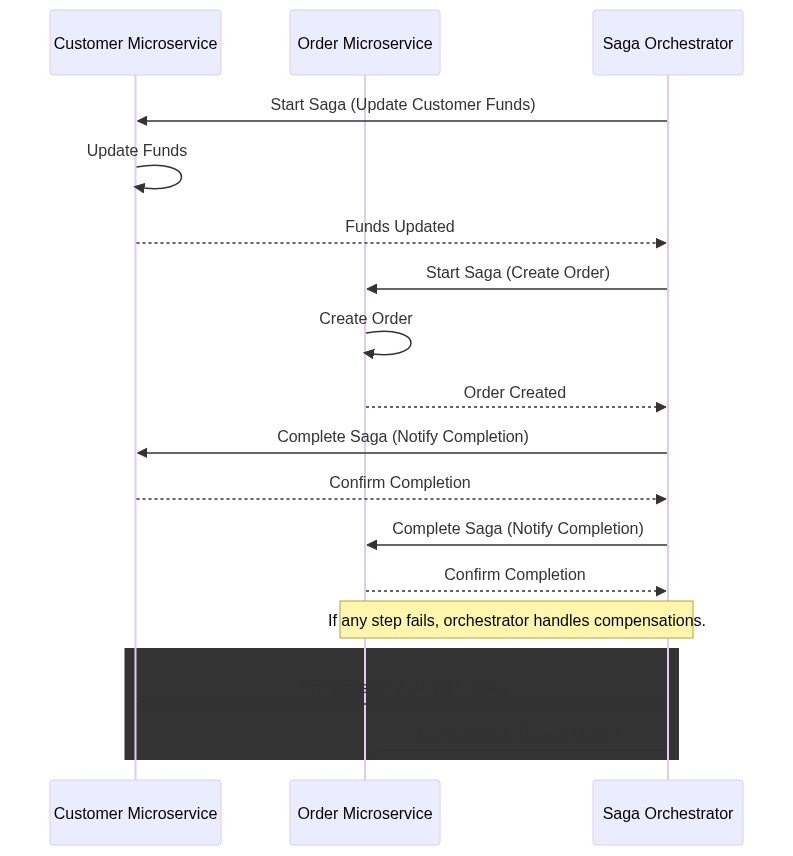

- Saga Pattern The Saga pattern breaks down a distributed transaction into a series of smaller, isolated transactions (or sagas), each with a compensating action in case of failure.

The Saga pattern can be implemented in two main ways: Choreography and Orchestration.

Choreography Pattern

In the Choreography pattern, each service involved in the saga knows about the next service and directly communicates with it.

There is no central coordinator; instead, each service participates in the saga by invoking the next service and handling its own compensations if needed.

Orchestration Pattern

In the Orchestration pattern, a central coordinator (orchestrator) manages the saga. It directs the flow of the saga, calling each service in sequence and handling compensations if any step fails. This central coordinator controls the entire transaction process.